xv6 scheduler and context switch

Hacking the xv6 kernel scheduling algorithm

We will explore the xv6 kernel scheduling algorithm as well as the context switch mechanism.

The source code for xv6 kernel is here.

I will not cover everything in this post, if you want to learn more, checkout those amazing references and resources at the end. This post covers context switch in term of timer-interrupts only, other cases may be for future blog posts.

Background

Scheduling

In the previous blog about /2024/09/01/adding-a-system-call-to-xv6.html[Adding a system call to XV6], we know that user programs are executed in a restricted manner. We know how the kernel provides a mechanism called system call for user that wants to access privilege resources on the hardware. The abstraction of process also gives our programs an illusion that we alone are using the hardware computing resources. The truth is most of us who studies computer science knows that, the kernel runs our processes by run one process, stop it and start running another repeatedly. This is called time-sharing. Time-sharing allows limited hardware resources to be shared among many processes, each process is given a small slice of processing time to execute their task.

Imagine this scenario, if we have only 1 CPU(1 core) on our machine, if a user process is using the CPU which means that the kernel is not running. How can the OS takes back control of the CPU from the user program?

If you are using a programming language like Go that implements concurrency using user thread, how does the Go runtime take back control from other Go routines?

In the context of limited direct execution, time-sharing allows the kernel to control how long user programs can run. By periodically forces user programs to give back the CPU to the controller, user programs can not uses resource forever. By giving the control back to the kernel, the kernel's scheduler can decide which processes to run. The scheduling algorithm is the kernel policy to decide which processes to run.

Multiplexing processes onto hardware processor

There are 2 cases when the kernel will switch from one process to another:

- OS periodically forces a switch when a process is executing in user space to the kernel space. This is called a timer-interrupt. In the previous blog post about /2024/09/01/adding-a-system-call-to-xv6.html[Adding a system call to XV6], we knows that when a system call is invoked, the user program must issue an interrupt instruction to transition to the kernel, the timer-interrupt is handled by the same mechanism. We will explore this later on in the xv6 kernel code.

-

When processes have to wait for device or pipe I/O to complete, when

parent process waits for a child process to exit or the

sleepsystem call.

Context Switch

When the OS wants to stop one process to run another, it must save the

context of currently running process. The kernel must save the old

thread's CPU registers and restore the saved register of the new

thread. For example, the kernel will save %eip (point to

next instruction) so that when it switches back, it will know which

instruction to continue execute.

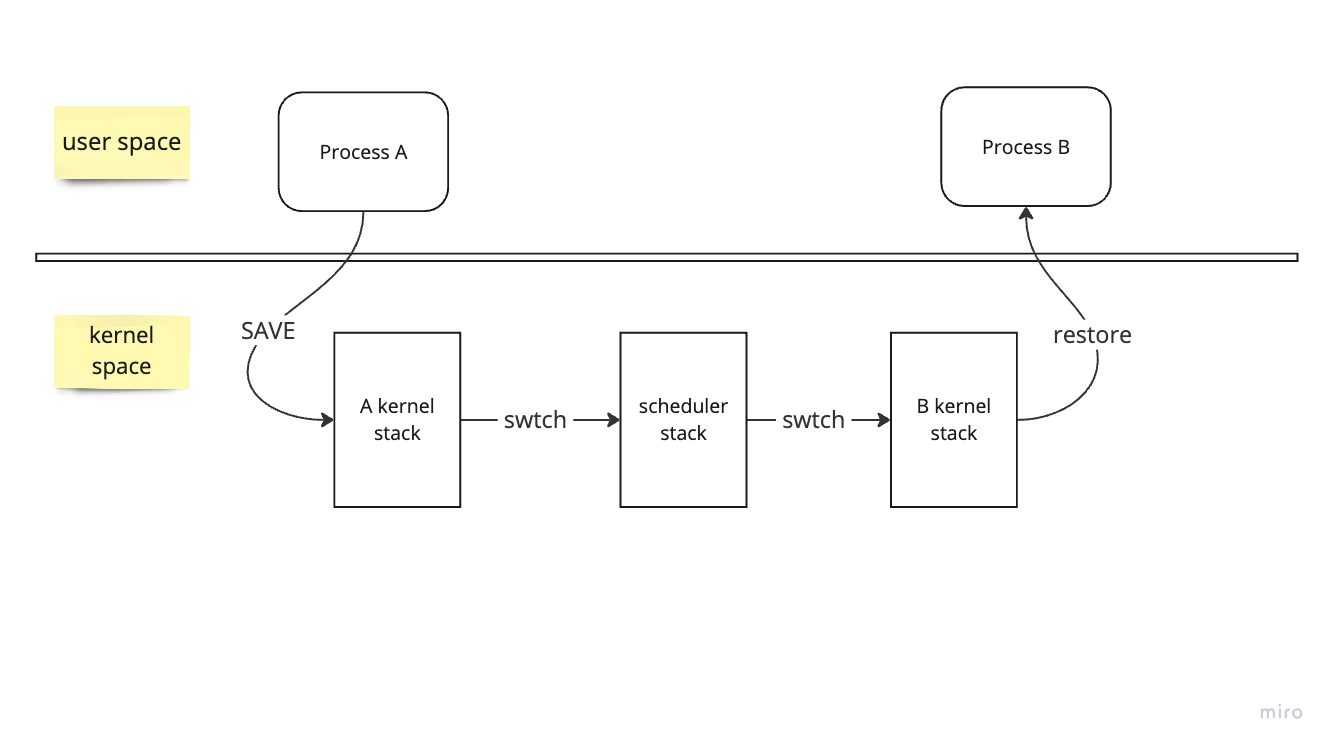

Context switching from one user process to another user process involves:

-

Transition from user space to kernel space by a system call (by

calling the

intinstruction), by interrupt. - From the A kernel thread, it will context switch to the CPU's scheduler thread. From here, the scheduler will make decision about which process to (in this case it will be B)

- a context switch to the B's kernel thread

- return to process B's user space

Now, let's dive into the code for context switch.

The code

States of OS

Before I show you the code of those context switch step above, let's look at some important data structure in the kernel.

// FILE: proc.c

struct {

struct spinlock lock;

struct proc proc[NPROC];

} ptable;

ptable is the process list shared by all processors.

Because of this, if we want to change the state of process we will

need acquire a lock. We can see that the limit of our processes is

NPROC which is 64. Here is the data structure of a

process:

// FILE: proc.h

struct context {

uint edi;

uint esi;

uint ebx;

uint ebp;

uint eip;

};

enum procstate { UNUSED, EMBRYO, SLEEPING, RUNNABLE, RUNNING, ZOMBIE };

// Per-process state

struct proc {

uint sz; // Size of process memory (bytes)

pde_t* pgdir; // Page table

char *kstack; // Bottom of kernel stack for this process

enum procstate state; // Process state

int pid; // Process ID

struct proc *parent; // Parent process

struct trapframe *tf; // Trap frame for current syscall

struct context *context; // swtch() here to run process

void *chan; // If non-zero, sleeping on chan

int killed; // If non-zero, have been killed

struct file *ofile[NOFILE]; // Open files

struct inode *cwd; // Current directory

char name[16]; // Process name (debugging)

};

-

pgdiris our page table which I will make another blog post. -

kstackis the process's kernel stack. In order for kernel to execute when process transition from user space to kernel space is that each process shares a part of their address space with the kernel. What this means is that the kernelcodeanddatasection exists in every process and is pointed to the same physical location in the memory. With this setup, when the process transition from user space to kernel space, kernel code can be executed. -

statepresents the state of our process.RUNNABLEis when our process can be run and it is waiting for the CPU to run.RUNNINGis when it is being executed. -

trapframeas discussed in the previous blog post will be used when the hardware jump to the trap handler. -

contextis the state of the process that needs to be saved during a context switch. You can see the%eipregister in here, which proves that during a context switch, the OS will execute our code at a difference location.

The Timer-interrupt

Timer interrupt is a kind of trap that the hardware will trigger every X ms. The OS will tell the hardware to find the timer interrupt handler when it is booted. Let's look at the previous C trap handler

// FILE: trap.c

void trap(struct trapframe *tf)

{

// ...

switch (tf->trapno) {

case T_IRQ0 + IRQ_TIMER:

if (cpuid() == 0) {

acquire(&tickslock);

ticks++;

wakeup(&ticks);

release(&tickslock);

}

lapiceoi();

break;

// ...

}

// ...

}

At the first switch case, we can find the trap number for timer

interrupts, it will update the ticks count and wakeup any process that

is waiting for the next ticks . It will only update the ticks count

for the first CPU because each CPU has its own timer and

interrupt and these timers may not be synchronized.

lapiceoi() will acknowledge the local interrupt so that

it can ready for next interrupts. The important code is further down

in this function.

I may cover

sleepandwakeupin future blog post

// FILE: trap.c

void trap(struct trapframe *tf)

{

// ...

if (myproc() && myproc()->state == RUNNING &&

tf->trapno == T_IRQ0 + IRQ_TIMER) {

yield();

}

// ...

}

This code will check if our process is running and if the trap number

is our timer interrupt. If it is, we will call yield to

give up the CPU. Let's look at the code in yield:

// FILE: proc.c

// Give up the CPU for one scheduling round.

void

yield(void)

{

acquire(&ptable.lock); //DOC: yieldlock

myproc()->state = RUNNABLE;

sched();

release(&ptable.lock);

}

What yield does is that it set the current process state

to RUNNABLE , because the process list is shared by

multiple CPUs that is why we need to acquire the

ptable.lock before we can change the state. Next we will

go and see what sched does.

// FILE: proc.c

void

sched(void)

{

int intena;

struct proc *p = myproc();

if(!holding(&ptable.lock))

panic("sched ptable.lock");

if(mycpu()->ncli != 1)

panic("sched locks");

if(p->state == RUNNING)

panic("sched running");

if(readeflags()&FL_IF)

panic("sched interruptible");

intena = mycpu()->intena;

swtch(&p->context, mycpu()->scheduler);

mycpu()->intena = intena;

}

sched will make sure that we can go into the scheduler

safely. Some conditions, we can already understand is that, we must

hold the ptable.lock, the process state must be

RUNNING. switch is where the context switch

happens. It will save the current process context and switch to the

context of the CPU's scheduler.

# Context switch

#

# void swtch(struct context **old, struct context *new);

#

# Save the current registers on the stack, creating

# a struct context, and save its address in *old.

# Switch stacks to new and pop previously-saved registers.

.globl swtch

swtch:

movl 4(%esp), %eax

movl 8(%esp), %edx

# Save old callee-saved registers

pushl %ebp

pushl %ebx

pushl %esi

pushl %edi

# Switch stacks

movl %esp, (%eax)

movl %edx, %esp

# Load new callee-saved registers

popl %edi

popl %esi

popl %ebx

popl %ebp

ret

Since we will interact with registers, this code is written in

assembly.

Don's worry, I will try to explain as much as possible

:D.

void swtch(struct context **old, struct context *new);This is how this assembly code looks like in C.

-

.globl swtchmakes theswtchlabel globally visible so that we can call this code in C. - In x86 convention (32-bit architecture specifically), function call is pushed onto the stack from right to left.

-

newwill be pushed onto the stack first, thenoldand finally the return address of this function.

movl 4(%esp), %eax # moves the content at address 4(%esp) which is the first argument (old) into register %eax

movl 8(%esp), %edx # moves the content at address 8(%esp) which is the second argument (new) into register %edx

-

the next 4 lines pushes registers that we saw in the

struct contextfrom above. Fields in struct are pushed in reversed order. The reasons%eipis not saved is that by the convention of x86, function call will push push%eiponto the stack which is the return address.

movl %esp, (%eax) # saves the current stack pointer into location pointed by %eax (old)

movl %edx, %esp # the stack pointer is set to the value in %edx (new). This switches the running thread

-

movl %edx, %esp: This line will change the stack to the context ofnew, means that we switch the running thread - now we at the new context, we restores the saved registers. Note that this is the next context's saved state.

retreturns from theswtch function

// at the start of swtch

[Higher Addresses]

...

return address <-- Pushed by `call swtch` <- %esp

&p->context <-- `new` (rightmost argument)

mycpu()->scheduler <-- `old` (leftmost argument)

[Lower Addresses]

So inside the call to yield, we will switch from the

current user process into the CPU's scheduler.

The Scheduler

void

scheduler(void)

{

struct proc *p;

struct cpu *c = mycpu();

c->proc = 0;

for(;;){

// Enable interrupts on this processor.

sti();

// Loop over process table looking for process to run.

acquire(&ptable.lock);

for(p = ptable.proc; p < &ptable.proc[NPROC]; p++){

if(p->state != RUNNABLE)

continue;

// Switch to chosen process. It is the process's job

// to release ptable.lock and then reacquire it

// before jumping back to us.

c->proc = p;

switchuvm(p);

p->state = RUNNING;

swtch(&(c->scheduler), p->context);

switchkvm();

// Process is done running for now.

// It should have changed its p->state before coming back.

c->proc = 0;

}

release(&ptable.lock);

}

}

The scheduler is per-CPU scheduler, which means each CPU has it owns

scheduler but they all share the same process list. The outer loop is

an infinite loop so that it never returns. The inner loop is to find

the next process to run. The xv6 scheduler is implemented using

round-robin algorithm which is our inner loop. When we found a process

that is

RUNNABLE, we will context switch to that process so that

it can be run.

At this point, from someone who knows how to code perspective but does

not know about the OS, they will think that after the

swtch, the loop will continue to run. But as we know, we

are now running at difference position until we call yield

again which will continue to run the line after swtch.

After the called to swtch, we are back to the called to

the function yield in trap.c. We were sent

to this point because of the timer-interrupt (Do you remember this

:D).

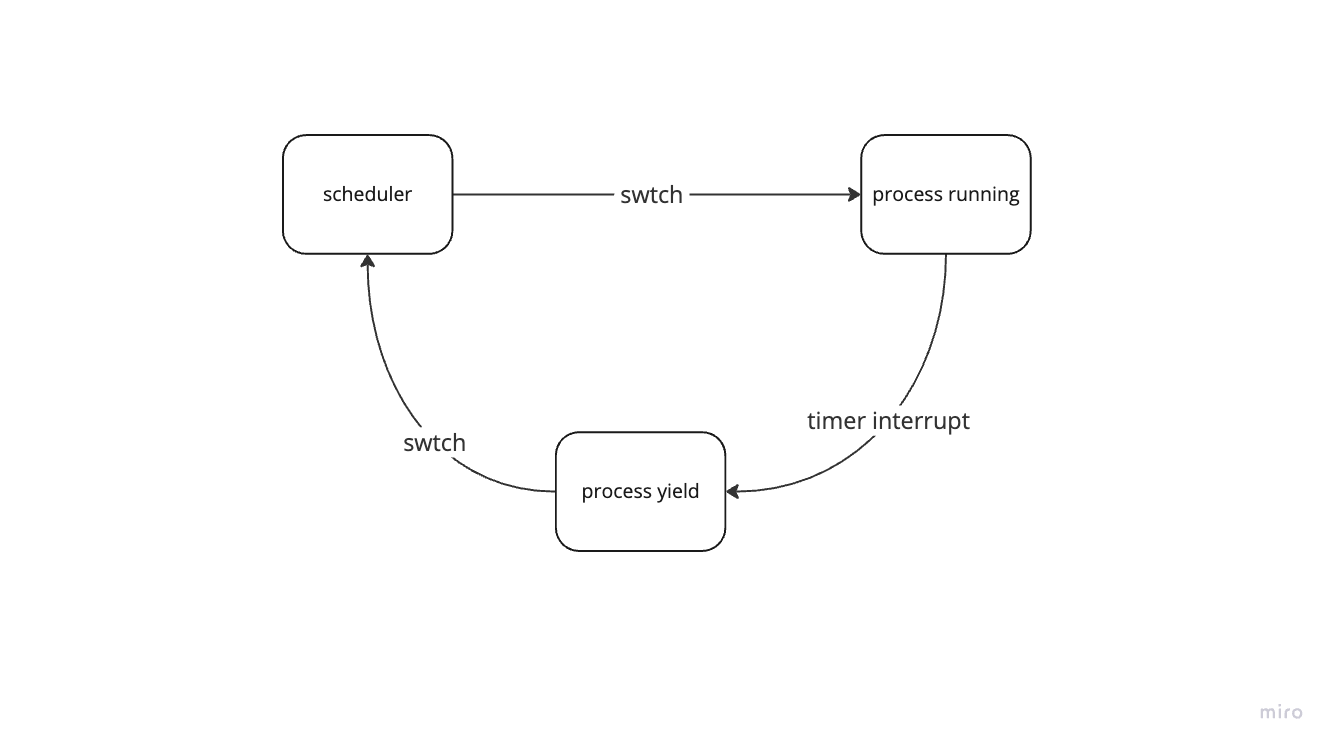

Here is where each code will be called to help you build your mental model.

swtchcalled by scheduler inproc.c-

after executing for X ms, timer-interrupt will force the process

into the

trap.c -

in

trap.c, the process will callyieldinproc.cto give up the CPU, which will callsched -

schedwill callswtchinswtch.Sto perform the context switch This process is perform repeatedly to switch from user process to the scheduler and back to user process.

Summary

-

OS uses timer interrupt to control how much a process can run.

-

At the end of the timer interrupt, the process will call

yieldto give up the CPU. -

During a context switch, the process will save the current context and switch to the context of the CPU's scheduler before the scheduler decides which process to run.